My parents taught me how to handle money. I spend it wisely, I don't buy stuff I cannot afford and I am super good at saving. I don't live on the edge. Now that I have my own lab, I notice that I am handling my lab budget in the same way. I want to make sure that we have enough money for experiments, which are always more difficult to interpret than planned and which always require more follow up than the aims section in my grants promised.

In a recent comic I read at the Node (originally from the Journal of Cell Science), Mole suggests keeping a monthly budget: if this month's funds run out, people can no longer order. They can read instead. Fortunately, my peeps read papers on their own and the only one who should be forced to spend more time reading the literature is me, alas.

I am slightly less strict than Mole (I must confess that I am also never sure whether Mole's advice is to be taken seriously - could someone fill me in on that?): I check throughout the year (every three months or so) to make sure that as a group we don't overspend on an annual basis. I know what that number is, because I do allocate a virtual amount of money to spend on reagents as well as on mice in a spreadsheet where I keep tabs of all my grants.

It was difficult to decide what strategy to follow at first. Both during my PhD and postdoc I was in the lab of established scientists who were pretty well off. They always had a bit of money here and there. I was hardly ever told not to order stuff (at least not for financial reasons - one of my PIs did have the occasional nasty habit of not signing off on orders if he didn't like the experiments you were planning to do). My rich mentors never taught or told me anything about budgeting.

Starting out on my own, funds were considerably more tight and, being the goody two shoes that I am, one of my worst fears was to overspend and to run out of money. At the same time, I didn't want my people to suffer from joining a small, junior lab. They shouldn't feel like they cannot order stuff when they have an exciting new idea. So I am educating my lab members like my parents educated me: Think about what you need before ordering, make sure we don't buy stuff we already have, try to find the cheapest price, but if you really need it: get it. So far, we are doing okay.

My biggest concern now is to decide how far I can stretch my grants when it comes to hiring new people. I am now facing a situation where I got a few "smaller" grants* and I am not sure what to do. The "problem"** is that this grant only pays for, say, half a PhD. In my ideal world, I would save that money until I would get another grant that would pay for the other half, but that's not how it works. The granting agencies want you to start spending that money within the fiscal year (so their bookkeeping checks out), but I am just not comfortable hiring someone when I am not sure I will have money to keep them for the second half of their contract as well. My risk averseness doesn't really serve me well here. I can already imagine the sleepless nights and the stress that is going to bring me. So how do others deal with this? Should I just get over it? Do others ask the department to tie them over in case something doesn't work out in the end? Any good or bad experiences are welcome in the comments.

* it's funny how quickly you start to think about a certain number as "small" simply because you are now also dealing with amounts of money you only used to hear about in the Powerball lottery.

**its also funny how having money can be as much as a problem as not having money, just a different kind of problem.

Young enough to remember what it was like to survive the Swamps of the PhD and the Valley of the Postdoc. Old enough to have travelled down the Tenure Track. Relieved and still amazed to find out I have now jumped through all the hoops. So now what?

My time flies

I really needed to be away from the lab for a bit. I was completely exhausted and I spent all of my free time surrounding Christmas and New Years sleeping 10 hours per night whenever I could. The rest of the time was spent sensibly watching Netflix, but only the good stuff, like season 9 of HIMYM (finally). On the Sunday before going back to the lab I still couldn't imagine being at work again, but then Monday came and before I knew it I was back to 10 hour days instead of 10 hour nights.

It's funny. You can be away from the lab and the world just keeps turning, but the minute you are back there is shitloads more stuff that needs to be done than time to actually get to even half of it. That's what I find the most depressing, I think.

I decided that I really needed to start keeping track of my time. And so I decided that I will try to schedule all meetings that are not about content on Mondays through Wednesdays, with Thursdays and Fridays solely dedicated to science. That means the odd experiment every now and again, writing grants and papers, and talking to my people about actual data. And, hopefully, reading a paper every now and then or simply think about a problem for 2 hours. Ah, 2 hours of undevoted attention without a knock on the door. Of course I can spend time on science on Mondays through Wednesdays, the challenge will be to keep Thursdays and Fridays free of teaching/politics/other stuff.

It worked this week. I just looked at my calendar and of course there are already appointments seeping into Thursday. Man, this is about as tough as sticking to some crazy new diet. But here too, there is no failure, there is only a chance to begin again.

The second thing I started to do was actually logging my time. I want to do that for a couple of weeks straight to really see where my time goes. The first thing I noticed was how easily I let myself be interrupted. When someone comes in, I never send anyone away. I always jump up to help/talk/listen. And then it takes me a while to get back into what I was doing. Or, worse, I forgot what I was doing and start up something else. Total time drain! What a wake up call.

Also: e-mail. I am trying to NOT answer e-mail first thing in the morning. Instead, I do it once mid-day around lunch and once in the evening, before going home. Which is risky, because it means there will never be a clean line of being finished and so I will stay at work until forever (which is a risk anyways, because I am definitely an evening person).

I also try to eat better, because I can no longer pretend that chocolate cookies at 11 pm are a decent dinner for a grown up. That's why I had home-made salad on Monday and Tuesday, cooked a real meal at home (at 10 pm, but that's still progress). And then I fell off the wagon and had pizza on Thursday and cookies for dinner on Friday. I swear I need someone to take care of me. Oprah would not approve.

To be continued and, once I have logged stuff for a month or so (which takes a lot of time, actually, because since I apparently let my self be so easily distracted/claimed, I am logging lots of 15 minutes this, 15 minutes thats) I will be able to make bar graphs to see where the time goes. Yay.

It's funny. You can be away from the lab and the world just keeps turning, but the minute you are back there is shitloads more stuff that needs to be done than time to actually get to even half of it. That's what I find the most depressing, I think.

I decided that I really needed to start keeping track of my time. And so I decided that I will try to schedule all meetings that are not about content on Mondays through Wednesdays, with Thursdays and Fridays solely dedicated to science. That means the odd experiment every now and again, writing grants and papers, and talking to my people about actual data. And, hopefully, reading a paper every now and then or simply think about a problem for 2 hours. Ah, 2 hours of undevoted attention without a knock on the door. Of course I can spend time on science on Mondays through Wednesdays, the challenge will be to keep Thursdays and Fridays free of teaching/politics/other stuff.

It worked this week. I just looked at my calendar and of course there are already appointments seeping into Thursday. Man, this is about as tough as sticking to some crazy new diet. But here too, there is no failure, there is only a chance to begin again.

The second thing I started to do was actually logging my time. I want to do that for a couple of weeks straight to really see where my time goes. The first thing I noticed was how easily I let myself be interrupted. When someone comes in, I never send anyone away. I always jump up to help/talk/listen. And then it takes me a while to get back into what I was doing. Or, worse, I forgot what I was doing and start up something else. Total time drain! What a wake up call.

Also: e-mail. I am trying to NOT answer e-mail first thing in the morning. Instead, I do it once mid-day around lunch and once in the evening, before going home. Which is risky, because it means there will never be a clean line of being finished and so I will stay at work until forever (which is a risk anyways, because I am definitely an evening person).

I also try to eat better, because I can no longer pretend that chocolate cookies at 11 pm are a decent dinner for a grown up. That's why I had home-made salad on Monday and Tuesday, cooked a real meal at home (at 10 pm, but that's still progress). And then I fell off the wagon and had pizza on Thursday and cookies for dinner on Friday. I swear I need someone to take care of me. Oprah would not approve.

To be continued and, once I have logged stuff for a month or so (which takes a lot of time, actually, because since I apparently let my self be so easily distracted/claimed, I am logging lots of 15 minutes this, 15 minutes thats) I will be able to make bar graphs to see where the time goes. Yay.

The end of year 2

Although the Gregorian calendar and my tenure track clock do not run entirely in sync, I find myself at the end of 2015 as well as at the end of my second year of the tenure track right around the same time. Looking back on 2015 is quite easy: virtually all I did was work. The friends I still have left will confirm this.

Looking back on year 2 of the TT is a bit scary. It means I'm almost halfway done and people are expecting output. One of the most ridiculous things in my bit of the world is the fact that the evaluation procedure at the end of the tenure track is pretty much spelled out at the start. There was a bit of room for negotiation before I signed the contract (but not that much, really) and it was made very clear to me that it was either in or out: if I didn't hit my targets, it would be over. In contrast to other places in the world, where I have seen examples of TT evaluations that actually leave some room for interpretation (e.g. "good output in terms of papers in respected journals"), the hoops I have to jump through leave very little room for anything. I need to publish X numbers of papers with at least Y number of impact factors. And those are the demands that still make some sense... With contracts like that you run the risk that people are going to sit there and make sure they tick all of the boxes. The problem is: that's not the kind of scientist I am. That's not the kind of human being I am. I like to feel like I am part of the place I work in. I like to do things that may pay off in the long run, rather than ensure I pass the next TT hurdle. This is academia, for crying out lout. I am not some kind of sales person that is expected to hit a certain quotum. Except for that, well, I am.

Personally, I think that if I set up an awesome network or a new line of research that attracts the interest of students that should count for something. But alas, it is not measurable and therefore it would be wiser for me to focus on blindly getting papers out than on some of the other things that I think are important for me to grow as a scientist as well.

And so, looking back on year 2, I feel pretty good about actually making my midterm evaluation (coming up at the end of year 3). I ticked all of the midterm boxes, as far as I can tell. I was fortunate enough to actually get some grant proposals funded, or it would have been bye bye already. But most importantly, I did well by just being me and by not focusing too much on what the powers that be actually demanded of me. Being a good scientist and teacher, it turns out, has sufficed so far. A scientist and teacher that worked her ass off, had two weeks off during summer and spent those sick and exhausted in bed and who barely made it to the Christmas break alive, but hey, those are details.

What I am worried about, however, is those X's and Y's that need to match up between reality and that stupid ass contract at the end of year 5. Oh, I could go on and on about how ridiculous it is to put easy-to-tick-off numbers and qualifiers on whether or not someone is a good scientist. I also tell it to everyone who wants to listen, including upper management. So it's not like I am blindly playing along with the system pretending it's all roses and fairytales. But I am finding that I am developing a pokerface when answering questions about my "progress", even though I am quietly shitting my pants.

It has taken up so much time and energy to set up the team and the experimental pipeline and now that everything is running smoothly for the past 6 months or so, papers should really start to come out this year. At least, I am getting more and more questions about this from the peeps that will actually be evaluating whether Iam worthy of tenure ticked all my boxes at the end of the run. So I put on a brave smile and tell them we are "on track", but deep down inside I know that "on track" merely means we haven't derailed. We've barely left the station for most projects, encountering bumps in the road and troubleshooting like the cool science cowboys that we are. We are picking up steam but we're far from there yet. I am just hoping that scientific output (at least the one measured in papers) doesn't have to show a linear increase. Otherwise I might as well start packing up already.

Unfortunately there is a move in the future, which means massive disruption and delays, since I will have to set up everything at a new site again. Plus I will be required (as I was much of last year) to devote my time to designing lab spaces and office spaces and fights for equipment so my people won't suffer too much while I really should be focusing on science. All of this scares the bejezus out of me, but I'm not letting anyone in on that little secret. At least not the people that need to think I have my shit together.

Looking back on year 2 of the TT is a bit scary. It means I'm almost halfway done and people are expecting output. One of the most ridiculous things in my bit of the world is the fact that the evaluation procedure at the end of the tenure track is pretty much spelled out at the start. There was a bit of room for negotiation before I signed the contract (but not that much, really) and it was made very clear to me that it was either in or out: if I didn't hit my targets, it would be over. In contrast to other places in the world, where I have seen examples of TT evaluations that actually leave some room for interpretation (e.g. "good output in terms of papers in respected journals"), the hoops I have to jump through leave very little room for anything. I need to publish X numbers of papers with at least Y number of impact factors. And those are the demands that still make some sense... With contracts like that you run the risk that people are going to sit there and make sure they tick all of the boxes. The problem is: that's not the kind of scientist I am. That's not the kind of human being I am. I like to feel like I am part of the place I work in. I like to do things that may pay off in the long run, rather than ensure I pass the next TT hurdle. This is academia, for crying out lout. I am not some kind of sales person that is expected to hit a certain quotum. Except for that, well, I am.

Personally, I think that if I set up an awesome network or a new line of research that attracts the interest of students that should count for something. But alas, it is not measurable and therefore it would be wiser for me to focus on blindly getting papers out than on some of the other things that I think are important for me to grow as a scientist as well.

And so, looking back on year 2, I feel pretty good about actually making my midterm evaluation (coming up at the end of year 3). I ticked all of the midterm boxes, as far as I can tell. I was fortunate enough to actually get some grant proposals funded, or it would have been bye bye already. But most importantly, I did well by just being me and by not focusing too much on what the powers that be actually demanded of me. Being a good scientist and teacher, it turns out, has sufficed so far. A scientist and teacher that worked her ass off, had two weeks off during summer and spent those sick and exhausted in bed and who barely made it to the Christmas break alive, but hey, those are details.

What I am worried about, however, is those X's and Y's that need to match up between reality and that stupid ass contract at the end of year 5. Oh, I could go on and on about how ridiculous it is to put easy-to-tick-off numbers and qualifiers on whether or not someone is a good scientist. I also tell it to everyone who wants to listen, including upper management. So it's not like I am blindly playing along with the system pretending it's all roses and fairytales. But I am finding that I am developing a pokerface when answering questions about my "progress", even though I am quietly shitting my pants.

It has taken up so much time and energy to set up the team and the experimental pipeline and now that everything is running smoothly for the past 6 months or so, papers should really start to come out this year. At least, I am getting more and more questions about this from the peeps that will actually be evaluating whether I

Unfortunately there is a move in the future, which means massive disruption and delays, since I will have to set up everything at a new site again. Plus I will be required (as I was much of last year) to devote my time to designing lab spaces and office spaces and fights for equipment so my people won't suffer too much while I really should be focusing on science. All of this scares the bejezus out of me, but I'm not letting anyone in on that little secret. At least not the people that need to think I have my shit together.

Weekend

With CNN covering the bloody attacks in Paris in the background, I am spending all of Saturday behind the computer. There is so much on the to do list, that I have to admit defeat: the list will never be finished. Ever. It will just grow and, if I'm lucky, every now and then I will be able to make a dent in it by softly pushing in the borders like a harmonica.

During the week I am so busy with who-knows-what, that the actual science has to wait until the weekend. And this is not even what I used to call science (as in: involving a pipette), but the stuff I now call science.

So after spending yesterday on politics, grading a student proposal (late) and a student thesis (also late) today I reviewed a manuscript for a journal (which was... late), a manuscript draft for a colleague that may become a collaboration (which I also promised to have finished a week ago), and worked on the program for a meeting I am organising next year.

During the week I am so busy with who-knows-what, that the actual science has to wait until the weekend. And this is not even what I used to call science (as in: involving a pipette), but the stuff I now call science.

So after spending yesterday on politics, grading a student proposal (late) and a student thesis (also late) today I reviewed a manuscript for a journal (which was... late), a manuscript draft for a colleague that may become a collaboration (which I also promised to have finished a week ago), and worked on the program for a meeting I am organising next year.

A day in the life of a newish PI: 1 October

Following in the footsteps of the New PI over at thenewpi.blogspot.com, I decided to track my whereabouts today so that others (or wannabe PI's) can get a glimpse of what it's really like. I missed the first opportunity on 17 September, because I was too busy running around and I didn't keep track of my time. But better late than never, and so here I present: my October 1st.

I guess today was a good day. I actually spent time on science.

I woke up at 8:30. That is not typical at all, but I was completely exhausted after an intense stretch of teaching. I taught three 9 am classes on Monday (3 hours), Tuesday (3 hours) and Wednesday (1 hour) and spent each of the evenings before preparing until well past 1 am. On Tuesday night I also gave a public outreach lecture and on top of everything I was teaching the Wednesday morning class in another city, which meant that I had to leave home at 7 am. I don't know how US presidents do it, but I tend to function less well after a couple of nights with only 5 hours of sleep.

8:30 - 9:00 I made coffee and checked my calendar (I switched from paper to iCal last year) and to do lists (it had a bit of a learning curve, but now I would be nothing without "Things") over breakfast (leftover pancakes - sad, I know). I then did what you are supposedly not to do at the start of your day, which is check e-mail (some say this will distract you from doing what you had actually planned to do). However, I had been postponing answering some e-mails because I was busy and there were also just a few small ones to get out of the way, including some teaching correspondence which mostly had to do with me not having access to a database I was supposed to be able to get into and the teaching administration people blaming it on "the system".

9:00 - 11:00 I went over the slides for the lecture I had to teach in the afternoon. Unlike the course I was teaching on Monday and Tuesday (which isI new and therefore takes forever to prepare because I have to generate all of the material from scratch), I did teach this class before. So I dug up my slides from last year and checked if any of them needed updating (I try to incorporate a bit of my own research and/or new findings from the literature into each class as much as possible) or whether I wanted to change the order. I didn't make all that many changes, but it still took me two hours for a two hour class. I don't think that is too uncommon.

11:00 - 11:30 I took a shower and got dressed, because I had to be at journal club at noon. I wasted ten precious minutes looking for clean underwear and two matching socks. While searching, I transferred my lecture from the iMac to the MacBook. Thank goodness for Wifi and Dropbox. Unfortunately, my laundry quest meant I was going to be late, because it takes more than half an hour to get to work.

11:30 - 12:10 I biked to work and ran to journal club.

12:10 - 14:00 Nice journal club session. We tore apart a Nature paper. As a PhD student and postdoc I never was super fond of journal clubs, although I could see their value. It just felt like they took me away from my 'real work'. These days, they are a welcome interruption and they actually count as "doing science". It also never ceases to amaze me how much more you get out of a paper when you read it with a whole group of people with different backgrounds.

14:10 - 14:55 I ran down, bought lunch and a coffee, ate it on the way back to my room, checked in with my people to see how everyone was doing and to inquire about the mice we operated on last night until 8 pm. Everyone was doing fine. Yay. Then I had a few discussion with different people about political issues (not the Hillary/Trump ones but the University/Career kind). I kicked everyone out of my office five minutes before my class started.

14:55 - 15:00 I ran down the stairs and set up my laptop. I am a pro now. Getting into the room early to make sure everything is working is for sissies. I can bluff my way through any audiovisual system. Although this room had a smart board and I didn't know how to combine beaming and writing so I ended up explaining Cre/lox technology using the old-fashioned whiteboard on the side wall. I opened the windows to let oxygen into the room, because I didn't want everyone to fall asleep.

15:00 - 17:00 I taught my class (to a small group of MSc students). It went well, they seemed to like it enough and I taught them new stuff (I regularly check to see how it connects to what they already know) and they stayed awake. What more can you wish for.

17:00 - 19:00 I read a manuscript that I had to review. The deadline was the day before yesterday. It's hard to believe that only two to three years ago I was one of those people who aways had everything finished in time, preferably a couple of days before a deadline. Now I am constantly chasing them, it seems. I was reviewing this manuscript with my postdoc (after asking permission from the editor) as part of the postdoc's academic training. Plus it's nice to exchange thoughts and talk about science, even if it is someone else's. This was the first review for this postdoc, so I needed to evaluate the review draft as well as the manuscript. Big papers (Cell, Nature and the like) still take me at least a day to review (usually with at least a night's sleep in between sessions), but this was a smaller one and I was able to evaluate everything in two hours.

19:00 - 20:30 My postdoc and I went over the manuscript, edited the first draft of the review, finalised it and uploaded it to the journal online review system. When we were done I had a new invitation for another review waiting in my mailbox.

20:30 - 21:30 I biked home and stopped along the way at a supermarket to buy food. Dinner was some battered fish from the oven with a bit of cucumber and a glass of wine. My mom is right. I should take better care of myself.

I guess today was a good day. I actually spent time on science.

I woke up at 8:30. That is not typical at all, but I was completely exhausted after an intense stretch of teaching. I taught three 9 am classes on Monday (3 hours), Tuesday (3 hours) and Wednesday (1 hour) and spent each of the evenings before preparing until well past 1 am. On Tuesday night I also gave a public outreach lecture and on top of everything I was teaching the Wednesday morning class in another city, which meant that I had to leave home at 7 am. I don't know how US presidents do it, but I tend to function less well after a couple of nights with only 5 hours of sleep.

8:30 - 9:00 I made coffee and checked my calendar (I switched from paper to iCal last year) and to do lists (it had a bit of a learning curve, but now I would be nothing without "Things") over breakfast (leftover pancakes - sad, I know). I then did what you are supposedly not to do at the start of your day, which is check e-mail (some say this will distract you from doing what you had actually planned to do). However, I had been postponing answering some e-mails because I was busy and there were also just a few small ones to get out of the way, including some teaching correspondence which mostly had to do with me not having access to a database I was supposed to be able to get into and the teaching administration people blaming it on "the system".

9:00 - 11:00 I went over the slides for the lecture I had to teach in the afternoon. Unlike the course I was teaching on Monday and Tuesday (which isI new and therefore takes forever to prepare because I have to generate all of the material from scratch), I did teach this class before. So I dug up my slides from last year and checked if any of them needed updating (I try to incorporate a bit of my own research and/or new findings from the literature into each class as much as possible) or whether I wanted to change the order. I didn't make all that many changes, but it still took me two hours for a two hour class. I don't think that is too uncommon.

11:00 - 11:30 I took a shower and got dressed, because I had to be at journal club at noon. I wasted ten precious minutes looking for clean underwear and two matching socks. While searching, I transferred my lecture from the iMac to the MacBook. Thank goodness for Wifi and Dropbox. Unfortunately, my laundry quest meant I was going to be late, because it takes more than half an hour to get to work.

11:30 - 12:10 I biked to work and ran to journal club.

12:10 - 14:00 Nice journal club session. We tore apart a Nature paper. As a PhD student and postdoc I never was super fond of journal clubs, although I could see their value. It just felt like they took me away from my 'real work'. These days, they are a welcome interruption and they actually count as "doing science". It also never ceases to amaze me how much more you get out of a paper when you read it with a whole group of people with different backgrounds.

14:10 - 14:55 I ran down, bought lunch and a coffee, ate it on the way back to my room, checked in with my people to see how everyone was doing and to inquire about the mice we operated on last night until 8 pm. Everyone was doing fine. Yay. Then I had a few discussion with different people about political issues (not the Hillary/Trump ones but the University/Career kind). I kicked everyone out of my office five minutes before my class started.

14:55 - 15:00 I ran down the stairs and set up my laptop. I am a pro now. Getting into the room early to make sure everything is working is for sissies. I can bluff my way through any audiovisual system. Although this room had a smart board and I didn't know how to combine beaming and writing so I ended up explaining Cre/lox technology using the old-fashioned whiteboard on the side wall. I opened the windows to let oxygen into the room, because I didn't want everyone to fall asleep.

15:00 - 17:00 I taught my class (to a small group of MSc students). It went well, they seemed to like it enough and I taught them new stuff (I regularly check to see how it connects to what they already know) and they stayed awake. What more can you wish for.

17:00 - 19:00 I read a manuscript that I had to review. The deadline was the day before yesterday. It's hard to believe that only two to three years ago I was one of those people who aways had everything finished in time, preferably a couple of days before a deadline. Now I am constantly chasing them, it seems. I was reviewing this manuscript with my postdoc (after asking permission from the editor) as part of the postdoc's academic training. Plus it's nice to exchange thoughts and talk about science, even if it is someone else's. This was the first review for this postdoc, so I needed to evaluate the review draft as well as the manuscript. Big papers (Cell, Nature and the like) still take me at least a day to review (usually with at least a night's sleep in between sessions), but this was a smaller one and I was able to evaluate everything in two hours.

19:00 - 20:30 My postdoc and I went over the manuscript, edited the first draft of the review, finalised it and uploaded it to the journal online review system. When we were done I had a new invitation for another review waiting in my mailbox.

20:30 - 21:30 I biked home and stopped along the way at a supermarket to buy food. Dinner was some battered fish from the oven with a bit of cucumber and a glass of wine. My mom is right. I should take better care of myself.

A new year

One of the best aspects of academia, is that you get to celebrate New Years twice per annum. The start of the 2015-2016 academic year (next week, where I'm at) offers a second opportunity for drafting resolutions. After a whole summer of preparing for a new class I am developing and teaching (which is turning out to be just about as much work as I had expected in my worst case scenario), these resolutions sound an awful lot like the ones from January. Make time for family and friends. Hell, make time for diner. Note to self: a non-microwave dinner.

So what does the new year have in store for me? Well, first of all I am going to be mid-way of (2.5 years into, that is) my tenure track some time in the spring of 2016. It's hard to believe how fast the time has gone. It feels like I just kinda know what I am supposed to be doing, but it means that I also have to start keeping an eye out for actual scientific output of my team (you know, publications).

When I started this job in 2013, I spent the first year like somewhat like the offspring of a sponge and a bouncing ball. I was so excited to have finally landed a position where I could set up my own lab and my own research. So excited to get a chance to do science my way, to become the mentor I'd always wanted to be and to figure out, step by step, what that actually was going to be. So excited to have the longest contract since high school, which felt like oceans of time spread out in front of me, with endless opportunities to branch out (while being aware of the danger of 'spreading to thin') into new directions, nurturing new collaborations, trying something crazy for a change. So excited to finally be learning something again myself. I knew I could do the postdoc thing, if I had to, but I wanted to grow as well. So I soaked it all up. The politics. The shenanigans. The organisational hassles. The lab management. I was thrilled, even if I had no clue what I was doing.

It took about a year and a half to get the proper funding (and hire the right people using said funding), which leaves me with the feeling that it only seems like things have been up and running for six months or so. Which means that I am almost midway of my tenure track, while in reality we've barely picked up momentum. That's a bit of a scary thought too, I must admit. So I'll just keep on doing what I have been doing: taking it one day at a time, while occasionally glancing at my whiteboard, which holds my grand master scheme for total world domination.

So what does the new year have in store for me? Well, first of all I am going to be mid-way of (2.5 years into, that is) my tenure track some time in the spring of 2016. It's hard to believe how fast the time has gone. It feels like I just kinda know what I am supposed to be doing, but it means that I also have to start keeping an eye out for actual scientific output of my team (you know, publications).

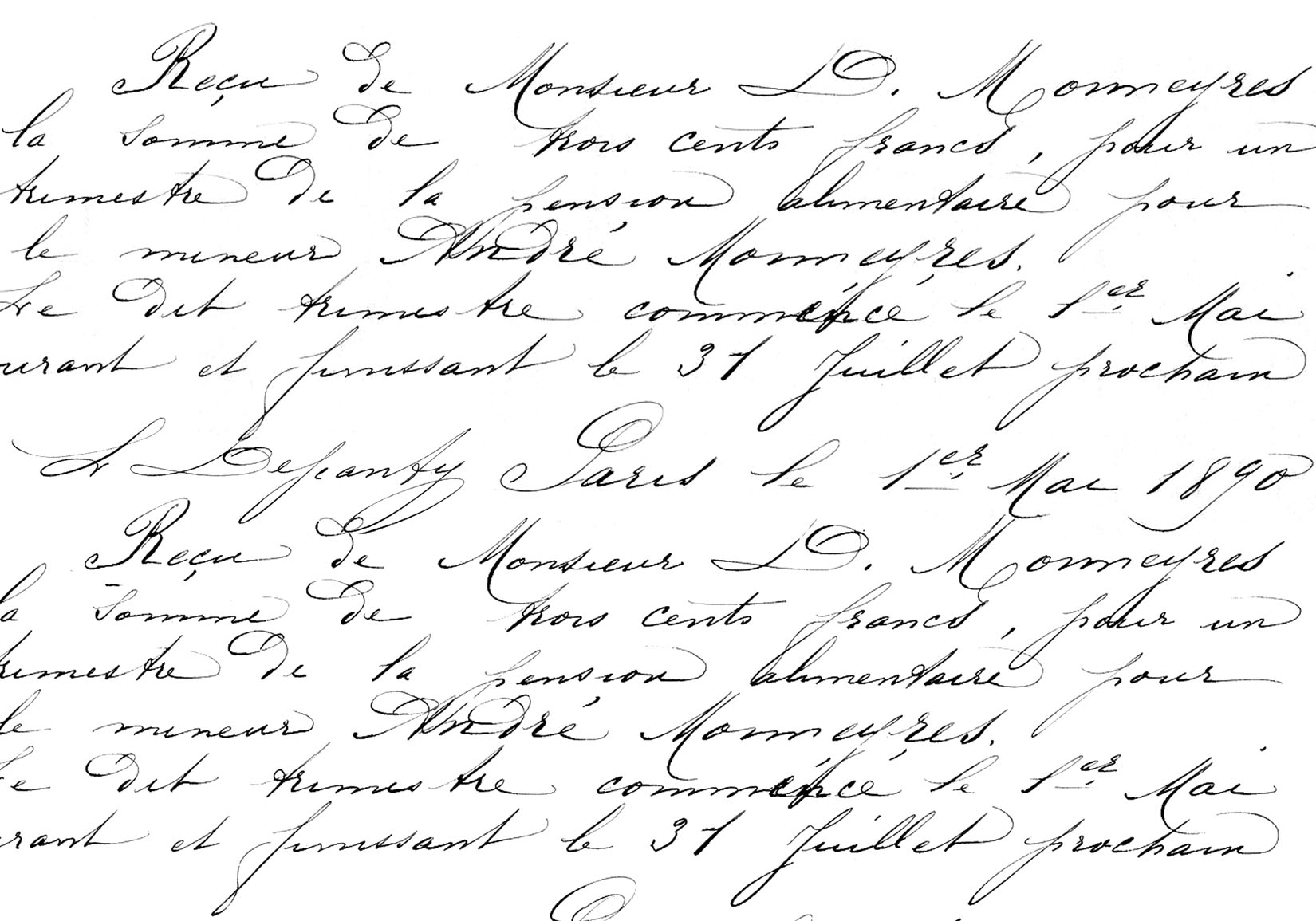

|

| What I felt like the first year. |

When I started this job in 2013, I spent the first year like somewhat like the offspring of a sponge and a bouncing ball. I was so excited to have finally landed a position where I could set up my own lab and my own research. So excited to get a chance to do science my way, to become the mentor I'd always wanted to be and to figure out, step by step, what that actually was going to be. So excited to have the longest contract since high school, which felt like oceans of time spread out in front of me, with endless opportunities to branch out (while being aware of the danger of 'spreading to thin') into new directions, nurturing new collaborations, trying something crazy for a change. So excited to finally be learning something again myself. I knew I could do the postdoc thing, if I had to, but I wanted to grow as well. So I soaked it all up. The politics. The shenanigans. The organisational hassles. The lab management. I was thrilled, even if I had no clue what I was doing.

It took about a year and a half to get the proper funding (and hire the right people using said funding), which leaves me with the feeling that it only seems like things have been up and running for six months or so. Which means that I am almost midway of my tenure track, while in reality we've barely picked up momentum. That's a bit of a scary thought too, I must admit. So I'll just keep on doing what I have been doing: taking it one day at a time, while occasionally glancing at my whiteboard, which holds my grand master scheme for total world domination.

How to get a job interview: 5 Tips for writing your cover letter and CV

All of a sudden I am at the other side of the table. The first time I had to hire someone in the lab I was probably as nervous and sleep deprived as the candidate, but I tried really hard not to show it. It's scary. Picking those first few people with whom you want to build your team is of great importance. You don't want someone to quit after a year, because they suddenly realise they want to do something else. You don't want troublemakers: when your lab is still really small, one sour apple is going to spoil everything. You hope for someone smart and creative and you take a guess. In the end, there is no certainty.

What struck me however, was how easy is it is to make the first selection. And with 'first selection' I mean deciding who goes on the 'yes definitely invite to an interview', 'well, maybe' and 'nope' pile. As it turns out, many candidates have no clue how to write a letter (or how to present their CV) in such a way that they even remotely stand a chance.

So here are my 5 tips for increasing your chance to be invited to an interview (and I guess most of these tips hold for non-academia as well). Now some of these may sound like nitpicking. But remember: the job market is tough. For every tiny mistake that you make, someone else will do a better job. And that someone else is going to land on the 'yes' pile. That could have been you. So make the extra effort!

1) Spell check. Spell check. Spell check.

If you make errors here, what subliminal message are you trying to convey? That you don't care about details? That you never think twice and reflect on what you do?

2) Grammar. Structure.

Eventually you are going to have to write a thesis. And papers. And reviews. And I'd like to be that period as productive and enjoyable as possible for all our sakes. So if you give me mumbo-jumbo in your letter and CV, what am I supposed to think? Even if you suck at writing, make sure you have your letter and CV checked by someone else! You want to dazzle me at the interview right? Bad writing is not going to land you one.

3) Dear Sir.

If you don't have the time to google my name and check my website to find out that I am a dear Madam (and preferably a dear Dr. and while we're at it let's go completely overboard and actually address me as Dear Dr. Lastname), why should I take the time to read your letter?

4) Layout.

Okay, maybe this is a pet peeve of mine. But if you cannot align stuff on paper? If it looks like your CV was created by aiming a letter gun at a piece of paper? That just gives me goosebumps allover. It sends me the subliminal message that you don't care about organisation and that everything you do is going to be a mess. Now my bench is not the neatest, but at least my CV has never betrayed that!

5) Make sense.

Get to the point. Why do you want this job and why should I want you? Saying that you admire my competitor's work? Yeah, there just might be days during which I have a hard time reading a complement in there. Why don't you write him a letter instead.

What struck me however, was how easy is it is to make the first selection. And with 'first selection' I mean deciding who goes on the 'yes definitely invite to an interview', 'well, maybe' and 'nope' pile. As it turns out, many candidates have no clue how to write a letter (or how to present their CV) in such a way that they even remotely stand a chance.

So here are my 5 tips for increasing your chance to be invited to an interview (and I guess most of these tips hold for non-academia as well). Now some of these may sound like nitpicking. But remember: the job market is tough. For every tiny mistake that you make, someone else will do a better job. And that someone else is going to land on the 'yes' pile. That could have been you. So make the extra effort!

1) Spell check. Spell check. Spell check.

If you make errors here, what subliminal message are you trying to convey? That you don't care about details? That you never think twice and reflect on what you do?

2) Grammar. Structure.

Eventually you are going to have to write a thesis. And papers. And reviews. And I'd like to be that period as productive and enjoyable as possible for all our sakes. So if you give me mumbo-jumbo in your letter and CV, what am I supposed to think? Even if you suck at writing, make sure you have your letter and CV checked by someone else! You want to dazzle me at the interview right? Bad writing is not going to land you one.

3) Dear Sir.

If you don't have the time to google my name and check my website to find out that I am a dear Madam (and preferably a dear Dr. and while we're at it let's go completely overboard and actually address me as Dear Dr. Lastname), why should I take the time to read your letter?

4) Layout.

Okay, maybe this is a pet peeve of mine. But if you cannot align stuff on paper? If it looks like your CV was created by aiming a letter gun at a piece of paper? That just gives me goosebumps allover. It sends me the subliminal message that you don't care about organisation and that everything you do is going to be a mess. Now my bench is not the neatest, but at least my CV has never betrayed that!

5) Make sense.

Get to the point. Why do you want this job and why should I want you? Saying that you admire my competitor's work? Yeah, there just might be days during which I have a hard time reading a complement in there. Why don't you write him a letter instead.

The Unknowns Unknowns

There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don't know we don't know.The other day I watched a documentary about Donald Rumsfeld. I found him intriguing, and a bit scary at times. He didn't even remember the quote himself and I cannot blame him. It is a pretty insane tongue twister. None of this however, is as intriguing, scary and insane as suddenly finding out that all the things you thought you knew in the lab, turn out to be things you do not know. Does this qualify as unknown knowns or unknown unknowns?

Anyway... we were trying to order filter tips the other day. It took us four hours and multiple phone calls to Greiner and Fisher to find out what we wanted and what the correct ordering number was. At least, I hope so. We'll see it when they get there.

Not nearly as complicated though as trying to order a bottle of BSA. Did you know that Sigma sells about two dozen? I've used three in my PhD and postdoc years, as it turns out (I paid some attention to the BSA, but not that much, I just grabbed it from the fridge. Come on folks, it's hard enough as it is to get everything going, I don't have days to think about albumin. Although of course I did. Because the stuff is bloody expensive. After we finally made a decision, it turned out we might be using far less that we were actually planning in the near future, since it looks like it's giving me a helluva lot of background in my Western Blots since I recently switched to a Licor/Odyssey system.

So that was my week. Troubleshooting Westerns, ordering filter tips and freeze dried cow protein. They don't give you the PhD for nothing.

It all looks the same from up close.

My first class

I have spent the better part of a decade (+/- a few years) focusing on research. I got out of bed, picked up a pipette and didn't put it down until I was ready to go back to sleep. Now that I have my own lab at The University, I also am going to spend part of my time teaching. Of course I have ample experience teaching students on a one-to-one basis. I have mentored quite a few undergraduates over the years. But when I was scheduled for my first 'real' lecture it suddenly hit me: I had not been forced to attendance in a college auditorium since I was an undergraduate myself.

So when preparing the lecture, I thought back to the things that I remembered from my own college professors. The quaint ones. The storytellers. The inspirational ones. That's what I would become. A source of inspiration that they would still remember fifty years from now...

I decided to sit in on a few lectures in the weeks prior to giving my own. Because how do you even talk to first year bachelor students? How do you know what they know and what they don't know? How do you talk differently to second year students? Or to third years? How do you maintain order? And, not unimportantly: How do you make them like you? Apparently constantly highlighting the stuff they're supposed to know for an exam is one way to score brownie points. But wait a second, I'm not here to score brownie points! I am here to inspire! To show them how wonderful biology is! How normal development and disease are closely intertwined! How cool it is to do science! How technology is developing at such an amazing pace! How great scientists of the past developed these incredible insights! I am...

... terrified. That's what I was when I walked into the room. I felt like I was a piece of bait, dropped into an ocean, waiting for the sharks to get me. Surely they could tell I had no clue what I was doing. I was hit by a serious case of imposter syndrome. This was definitely a fake-it-till-you-make-it moment.

Only 50% of the entire class showed up to begin with. Apparently, that's normal (I had counted attendance during one of my sit-ins). Out of those, about 25% appeared to pay some sort of attention. A couple of students were talking amongst themselves. They were over in a corner, I could ignore them and they didn't seem to bother anyone else and I was too damn scared to tell them to zip it or leave. Apparently they had mistaken the lecture hall for a Starbucks. These things happen. Same thing for the guy in the back row, who was wearing a headset while watching a movie on his laptop.

Just like that my whole Mary "I-will-be-firm-but-kind" Poppins courage sank somewhere to the bottom of the ocean. It was replaced by a slightly different mantra. The "Please-don't-throw-any-tomatoes-at-me" kind. No way would I tell these students to pay attention or leave! A quick risk assessment told me that if they would just choose to ignore my orders I would have no idea what to do next. If only I were six feet tall and male, I thought... Then I'd tell them...

Ah well, maybe in a next life.

In the end, no one threw tomatoes. And after the lecture a couple of students came up to me to ask for a bit more details on a part that they had found 'really interesting'. And that's when I realised that perhaps that's all I should ask for. If I can get to five students, that may be worth it. But is that really true? In this day and age, are there still teachers who can captivate a room full of 18 year olds? Should I start using clickers or soapbox or other gadgets that to my opinion only eat up time (and only provide room for technical glitches and the associated mockery) and don't really add anything?

I have decided that I will approach classroom teaching the same way I approach an experiment. Like a scientist. I will change a variable every time and see what happens. Next time, I will ask the group of students to stop talking. Maybe the time after, I will ask the student in the back row if we could plug in his laptop so we can all watch the movie. Or maybe I will think of something really brilliant, and they will all pay attention for two hours straight even though it is almost five o' clock in the afternoon and then they will spread the word and I will get 100% attendance from hence on.

I guess a girl can dream.

So when preparing the lecture, I thought back to the things that I remembered from my own college professors. The quaint ones. The storytellers. The inspirational ones. That's what I would become. A source of inspiration that they would still remember fifty years from now...

... terrified. That's what I was when I walked into the room. I felt like I was a piece of bait, dropped into an ocean, waiting for the sharks to get me. Surely they could tell I had no clue what I was doing. I was hit by a serious case of imposter syndrome. This was definitely a fake-it-till-you-make-it moment.

Only 50% of the entire class showed up to begin with. Apparently, that's normal (I had counted attendance during one of my sit-ins). Out of those, about 25% appeared to pay some sort of attention. A couple of students were talking amongst themselves. They were over in a corner, I could ignore them and they didn't seem to bother anyone else and I was too damn scared to tell them to zip it or leave. Apparently they had mistaken the lecture hall for a Starbucks. These things happen. Same thing for the guy in the back row, who was wearing a headset while watching a movie on his laptop.

Just like that my whole Mary "I-will-be-firm-but-kind" Poppins courage sank somewhere to the bottom of the ocean. It was replaced by a slightly different mantra. The "Please-don't-throw-any-tomatoes-at-me" kind. No way would I tell these students to pay attention or leave! A quick risk assessment told me that if they would just choose to ignore my orders I would have no idea what to do next. If only I were six feet tall and male, I thought... Then I'd tell them...

Ah well, maybe in a next life.

In the end, no one threw tomatoes. And after the lecture a couple of students came up to me to ask for a bit more details on a part that they had found 'really interesting'. And that's when I realised that perhaps that's all I should ask for. If I can get to five students, that may be worth it. But is that really true? In this day and age, are there still teachers who can captivate a room full of 18 year olds? Should I start using clickers or soapbox or other gadgets that to my opinion only eat up time (and only provide room for technical glitches and the associated mockery) and don't really add anything?

I have decided that I will approach classroom teaching the same way I approach an experiment. Like a scientist. I will change a variable every time and see what happens. Next time, I will ask the group of students to stop talking. Maybe the time after, I will ask the student in the back row if we could plug in his laptop so we can all watch the movie. Or maybe I will think of something really brilliant, and they will all pay attention for two hours straight even though it is almost five o' clock in the afternoon and then they will spread the word and I will get 100% attendance from hence on.

I guess a girl can dream.

Why there are days when I feel like president Obama

So this is it. I never thought I'd say this, but I miss the bench. I've been managing my own tiny little but ever so expanding lab for seven months (heavens, has it really been more than half a year already?) and it's come to the point where I already do not know how to program the latest PCR machine. Or the latest gossip. I used to be the one in the lab you would go to if you needed to know anything. As a postdoc, the lab had no secrets from me.

Now, I am out of the loop. Hungry for other people's data. It's not that I want them to work harder and produce more. But let's face it. That Western blot? That PCR gel? That's all the real science I am going to see in a day. The rest of the day is spent... doing what, exactly?

On a typical day I find myself on the phone (I used to dread making phone calls, boy, did I get over that pet peeve quickly) to fix all sorts of shit. Equipment that is not delivered on time. Equipment of which half the boxes gets delivered. Equipment that breaks down after a week of use. Computers that take six weeks to arrive (six weeks! it's enough to make you pull out all of your hair and then some). How is that even possible in this day and age? Purchasing departments that pretend to think with you, but which sometimes give of the impression they are thinking for you and than forget the thinking part while they are at it. Orders that are placed, but that then disappear into thin air. It's a never-ending struggle to just get things running smoothly. There are days where I've been really busy, only to go home at 9 pm to find that I have done nothing, apart from talking, calling and e-mailing about crap.

This must be what the president of the United States must feel like. You can come in with all sorts of ambitious goals and lofty ideas. You can make all sorts of promises on the campaign trail. When it comes down to it, you have to work within the budget and without getting into fights with other parties. In the end, your political agenda is controlled by outside forces and whatever te different agencies put on your plate.

Luckily however, I have come to the realisation that this is it. I am the wrinkle remover. I am responsible for making things in the lab run smoothly, if not for me, than for everybody working in the lab to produce those Western blots and PCR images I so yearn for to look at. I am solving problems, such that others can work without encountering them. I am the troubleshooter. Too bad that there isn't more time in a day to actually troubleshoot science, instead of the smudgy layers of 'processes' that seem to stand in the way of my lab advancing scientific knowledge. I have the feeling I'd better get used to this.

Now, I am out of the loop. Hungry for other people's data. It's not that I want them to work harder and produce more. But let's face it. That Western blot? That PCR gel? That's all the real science I am going to see in a day. The rest of the day is spent... doing what, exactly?

On a typical day I find myself on the phone (I used to dread making phone calls, boy, did I get over that pet peeve quickly) to fix all sorts of shit. Equipment that is not delivered on time. Equipment of which half the boxes gets delivered. Equipment that breaks down after a week of use. Computers that take six weeks to arrive (six weeks! it's enough to make you pull out all of your hair and then some). How is that even possible in this day and age? Purchasing departments that pretend to think with you, but which sometimes give of the impression they are thinking for you and than forget the thinking part while they are at it. Orders that are placed, but that then disappear into thin air. It's a never-ending struggle to just get things running smoothly. There are days where I've been really busy, only to go home at 9 pm to find that I have done nothing, apart from talking, calling and e-mailing about crap.

This must be what the president of the United States must feel like. You can come in with all sorts of ambitious goals and lofty ideas. You can make all sorts of promises on the campaign trail. When it comes down to it, you have to work within the budget and without getting into fights with other parties. In the end, your political agenda is controlled by outside forces and whatever te different agencies put on your plate.

Luckily however, I have come to the realisation that this is it. I am the wrinkle remover. I am responsible for making things in the lab run smoothly, if not for me, than for everybody working in the lab to produce those Western blots and PCR images I so yearn for to look at. I am solving problems, such that others can work without encountering them. I am the troubleshooter. Too bad that there isn't more time in a day to actually troubleshoot science, instead of the smudgy layers of 'processes' that seem to stand in the way of my lab advancing scientific knowledge. I have the feeling I'd better get used to this.

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)